Christopher Columbus, Richard Nixon and the Other Original American Sin — Part 2

20th Century Countercultures Burst Open the Doors of Perception Bringing Spiritual Epiphanies

Portugal, The Man’s Dummy features TankDog, existential dread and a catchy dance hook, seemingly backlash to Christian backlash

Cancelled by conquistadors in the 16th century, Native American spiritual practices and rituals involving psychedelic plants remained mostly underground for centuries, hidden away from wider Western law and consciousness.

The first psychedelic plant revered by Native Americans to breach containment was peyote cactus, containing hallucinogenic mescaline. Peyote’s traditional use was widespread in Central America at the time of Spanish conquest, traded long distances from its growing region (along today’s US-Mexico border.) Colonial leadership, bent on religious conversion, curtailed peyote trade and use, claiming association with the devil and human sacrifice. Suppression eased, however, with Mexican independence. Use spread in North America in the mid-19th century as US policy co-mingled tribes during brutal forced relocations.

In stark conditions on reservations in the southwestern USA, near peyote country, a new hybrid religion emerged. Solidifying in late 1800s, the Native American Church blends Christian and Native American beliefs, with ritualized peyote use as a central fixture. Adherents believe peyote to be a holy sacrament that facilitates communion with the monotheistic Great Spirit.

Increased usage among Native Americans would result in efforts to ban peyote and mescaline in the US, starting in 1888 with mixed local, state and national success for the following century. Such efforts only ended in 1996, when federal legislation formally recognized traditional peyote use among Native Americans as a legit religious practice.

Hardly contained, further proliferation would ignite moral panic, unfortunate attitudes coinciding with the temperance movement and alcohol prohibition. A 1923 NY Times screed, for example, decries the Native American Church as a “cult of death” with “false gods,” note that peyote is “nothing but an evil,” and dish falsehoods dressed as science. Despite the panic, perhaps partly due to it, peyote use escaped to impact wider Western culture earlier and more gradually than psilocybin mushrooms.

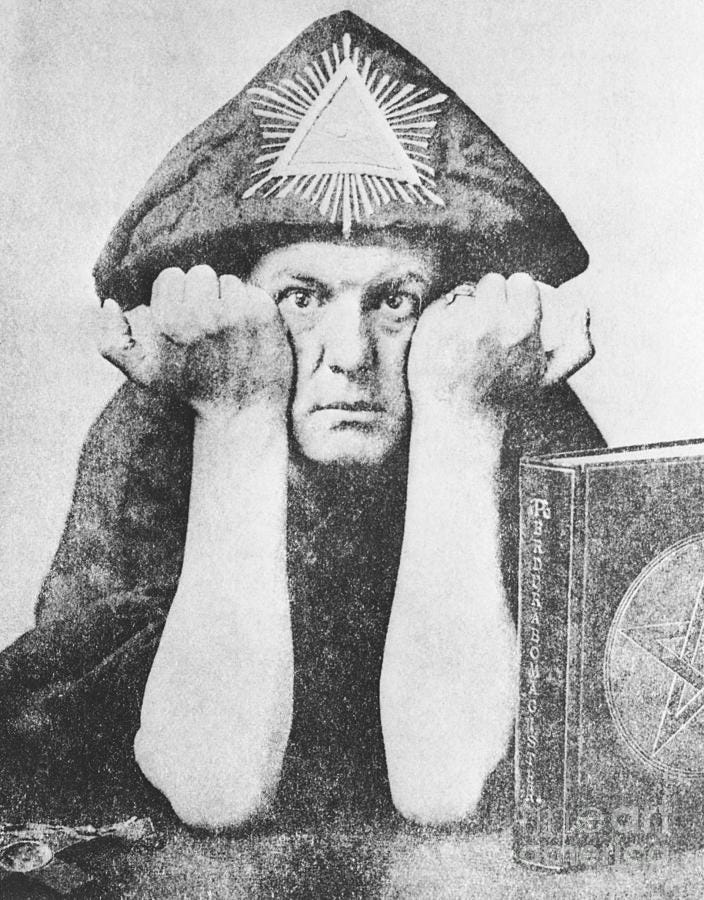

Magick: Occult Sensation

One cluster of early peyote proliferation was among the occult community, active and influential at the turn of the 20th century. Not beholden to Christian morality (or much else for that matter), several of the era’s occult figures revered mescaline for its ability to conjure hallucinations and alter consciousness.

Peyote juice among other intoxicants were often taken in so-called “magick” practices starting in the 1890s. Differentiating from “stage magic,” prominent occultist Aleister Crowley defined magick as the ritualization of one’s spiritual practices. While this “magick” may sound freaky-deaky, the Christian Eucharist is a familiar example. In that ritual, a religious leader appeals to a deity to perform a supernatural act (transubstantiation of bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ) then delivers it to a congregation for spiritual cleansing. So, any ritualized prayer seems to meet the definition for magick, not just the ones with black robes and weird chanting (which is what Crowley was up to.)

Occult figures were controversial to say the least. Unashamedly a promiscuous bisexual and drug user, Crowley publicly flouted conventions, thriving on the provocative. For this, in 1922, a time when sodomy was still illegal in the UK, British papers branded Crowley “The Wickedest Man in the World” . . . right around when fascism seized Europe. Among bohemians and intellectuals, however, Crowley enjoyed status as a bit of a high-society rock star before rock existed.

Occultist and writer Aleister Crowley engaged in a life-long freak out, blowing minds and taking on the establishment well ahead of the Merry Pranksters of the 60s

Earlier in 1904, after much peyote use and communing with a non-corporeal entity named Aiwass, Crowley became “The Prophet of the New Age,” founding a new religion. Called Thelema, the new faith borrowed from a wide variety of spiritual practices. Crowley leaned most heavily on Western esoteric principles from the insular Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, an influential occult group he’d recently exited. Linking that counter-cultural Western spiritualism (think Gnosticism, alchemy, Tarot etc) with Eastern practices like yoga and Hindu Vendantic mysticism, Crowley’s new religion rejects little aside from strict dogma and Christianity. As such, Thelema is believed the first New Age religion inspired by psychedelic experience.

Still alive today, Thelema’s core beliefs involve shedding society’s influences and restrictions, its only dogma: “Do what thou wilt.” Often misinterpreted to mean ‘satisfy every urge’ the imperative instead is to find and carry out one’s true purpose or calling. Doing so reveals one’s pure individuality, believed to be in harmony with the divine and therefore the Universe at large.

Doesn’t seem so bonkers, at least in those terms. But it seems to neglect the reciprocity and social responsibility baked into most spiritual traditions.

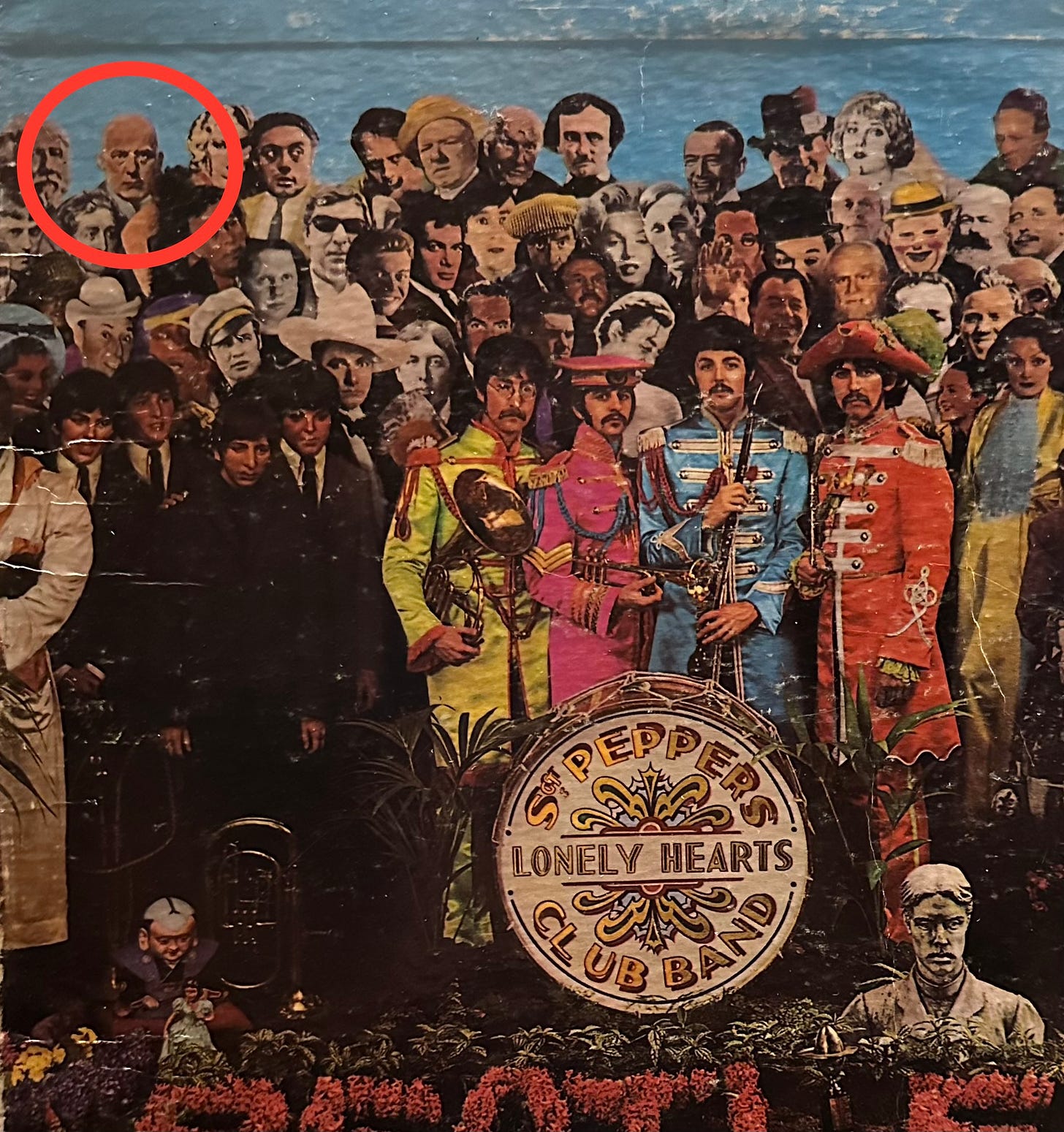

Crowley’s early psychedelic exploration and nonconformity earned him reverence among the later beat and hippie movements. The Beatles even included Crowley on the cover of St. Peppers

Fun fact: among Mussolini’s first dictates after consolidating power in 1923, was to deport Crowley and his followers at the weird Abbey of Thelema in Sicily. Their rampant individualism would clash with fascism’s demands for conformity. Nice work. Still, such unreservedly libertine attitudes might be criticized as oppositely extreme — self-centered, provocative and anti-social. Without any brakes on abusive behavior or demands for reciprocity, Thelema did not explicitly reject fascism. Some British Thelemites even became prominent fascists.

In any case, Crowley rejected fascism. He would also vehemently deny accusations of Satanism, citing a total rejection of Christian conceptions.

Sounds like something Satan might say.

More seriously, Crowley occasionally leaned into the accusations, sometimes referring to himself as Beast 666. But Crowley apparently did so for shock value and counter-cultural appeal rather than to denote actual Satan-worship. Having endured a harsh, fundamentalist upbringing, Crowley apparently rejected and rebelled against Christian orthodoxy. Crowley’s fame and legacy suggest he was not alone in that rebellion.

Similarly, John Gourley of Portugal, The Man (see music video at outset) endured a difficult Christian fundamentalist upbringing. He also flirts with psychedelia and anti-Christian themes 100 years later, sometimes provocatively invoking Satanic imagery. While such “FU” attitudes are understandable in the face of abuse and repression (perhaps appealing to many who have faced such) they also do not seem wholly healthy or productive. Makes for powerful and expressive music though.

Crowley’s careless attitudes about sex also netted him several children of different mothers, none of whom he could support. Meanwhile, his drug abuse resulted in a squandered inheritance, heroin and cocaine addictions, as well as the need for multiple nasal surgeries. For better or worse, Thelema would become associated with the later Satanism movement, developed after Crowley’s death in the 60s. Crowley’s legacy is certainly mixed and controversial, but undoubtedly important to proliferation of psychedelics and associated spirituality.

According to mescaline researcher Mike Jay, in the 1910s, influential poets W.B. Yeats and Ethel Archer tried peyote among a cocktail of intoxicants in séances and rituals with Crowley. Crowley also promoted and carried out several such magick ceremonies publicly as well, some of which featured peyote-spiked cocktails for honored guests. Generally, these were received terribly by an outraged press and public. Archer fictionalized the experiences into her 1932 novel, The Hieroglyph, further spreading knowledge of such practices.

Surreal Sacrament

Scientific understanding of mescaline’s effects took some time to materialize because of the strong biases. Some basic chemistry proved easier to master: mescaline was first isolated from peyote and characterized in 1896 by German chemist Arthur Heffter, then lab-synthesized in 1919 by Ernst Späth in Vienna. By 1920, in-the-know European psychologists and researchers could access synthetic mescaline via the Merck catalogue.

Right around then for some strange reason, mescaline and peyote penetrated avante garde arts. Most obviously, the Surrealism movement gaining steam in the 1920s seems inspired by (or at least dovetails with) psychedelic experiences and visions. The Surrealism movement’s focus on dreamworld imagery, stream-of-consciousness and the depths of the unconscious mind would galvanize fascination behind these hallucination-inducing substances at the very least.

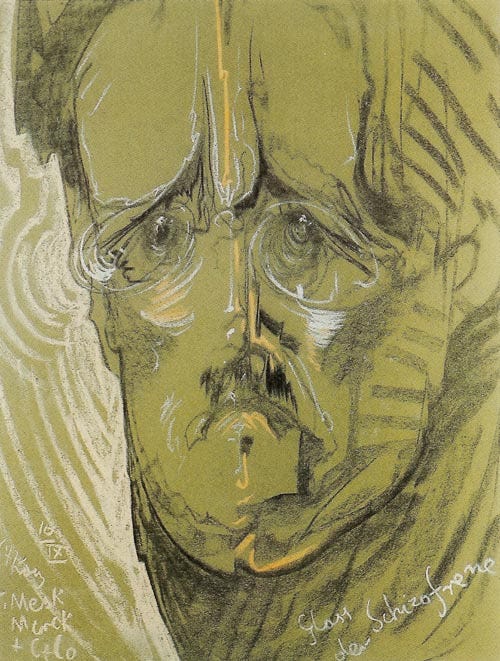

Portrait of Stephen Glass (1929), which artist Witkacy notes on the canvas was produced under the influence of Merck mescaline (as well as cocaine and vodka.)

Despite strong stigma, potent motivation to deny drug use, much mescaline experimentation among Surrealist artists is known. For example, Polish artist Stanislaw Witkiewicz (aka Witkacy) would be an early and vocal adopter. Witkacy found mescaline not only to enable creativity, but also help control his alcohol and tobacco addictions. Foreshadowing current developments nearly 100 years later in his 1930 study of Narcotics, Witkacy wrote:

I will just note my personal experiences with peyote, a drug that provides remarkable visions and profound glimpses into buried layers of the psyche and discourages the use of any other drug, above all alcohol. I consider its sporadic use utterly harmless, and given the absolute impossibility of forming a peyote habit, it ought to be used in every sanatorium where addicts of all stripes are treated

Automatic drawing pioneer André Masson unabashedly used hallucinogenic drugs to alter consciousness and assist in his work. Surrealist poet Henri Micheaux openly studied mescaline’s effects. Another poet, Anthonin Artaud, made a 1936 pilgrimage to Mexico in search of "the actual Myth of the Mystery, to become immersed in the original mythic arcane, to enter through them into the Mystery of Mysteries.” Participating in peyote ceremonies and descending into madness, Artaud immortalized his experiences in his 1937 Voyage to the Land of the Tarahumara. Many contend Salvador Dali, too, despite cheeky denials, was an early mescaline adopter, as hinted in his wild autobiography The Secret Life of Dali.

In the Tower of Sleep (1938) by André Masson

Visions for Depression-Era Visionaries

Artaud turns out NOT to be the lone literary figure to suffer a bad trip in the 30s. Influential writer and philosopher Jean-Paul Satre claimed a difficult mescaline experience left him with persistent hallucinations: “After I took mescaline, I started seeing crabs around me all the time” . . . “I mean they followed me into the street, into class.” Not all negative, Satre also recalled “I liked mescaline a lot” but also that “Everything seemed at once clammy and scaly, like some of the large serpents I have seen uncoiling themselves at Berlin zoo.”

Satre apparently felt overwhelmed, viscerally flooded with unpleasant, even disgusting sensations and hallucinations he found impossible to dispassionately observe. Satre called the experience “inconsistent and mysterious,” lacking any stable point of reference. Experience with mescaline, maybe too much of it, injected IV by a psychiatrist friend in 1935, profoundly impacted Satre’s thinking.

Satre and fellow French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty would compare notes on their mescaline experiences, both important figures emerging from Phenomenology. In this philosophical perspective, the rational and intellectual modes central to Western inquiry take a back seat to lived experience, whether sensed or imagined, compatible indeed with the psychedelic experience. Satre’s famous existential stance, obsessed with consciousness and free will, seemingly evolved from here, informed by the powerful hallucinatory experience alongside the horrors of WWII. Especially in his 1943 Being and Nothingness, Satre obsesses over the conflict between social pressures of conformity and one’s authenticity, evoking the same themes Crowley had. These would be central themes to fascism in mid-century Europe, of course, but also central to many psychedelic revelations.

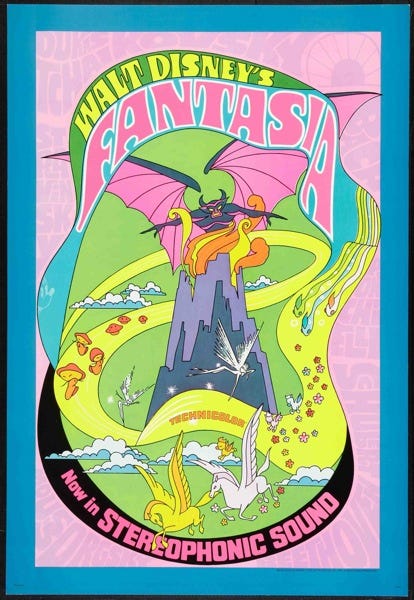

Playing up psychedelic appeal for the hippie generation, the trippy poster heralds the 1969 re-release of Fantasia

Mescaline use by mainstream visionaries and artists would remain more hidden. According to artist Paul Laffoley, Walt Disney and his creative team experimented with peyote in the 30s and 40s. Laffoley among others contend it “well known” that artists surrounding Black Mountain College (where many Disney creatives trained) regularly visited Chihuahua, Mexico to experience peyote ceremonies in the 30s and 40s. This would lead to regular usage back in the US among the wider community, including Disney animators like Walt Disney himself, according to the story. Unsurprisingly, Laffoley attributes Disney’s opus Fantasia being partially inspired by these experiences.

Obsessed with breaking new creative ground and making legitimate art, Walt Disney would also collaborate with contemporary far-out artists like Salvador Dali and Aldous Huxley. Immersed with all the right people and unconfined by conventions, Disney seems a likely early mescaline adopter. While no proof exists for Walt Disney’s psychedelic use specifically, his revolutionary animation studios flirted with much psychedelic imagery, at the very least, well before the term ‘psychedelic’ emerged. Perhaps this helped pave way for acceptance of these wild substances among a younger generation a few decades later.

Psychedelic imagery from Disney animation studios: Mickey’s Garden (1935), Dumbo (1941) and Fantasia (1940)

Pharmaceutical Revelations

LSD’s discovery in 1943 by Swiss drug chemist Albert Hofmann marked a profound moment in the history of pharmacology and philosophy. In search of stimulants for heart and lung heath, Hofmann stumbled onto LSD’s potent, mind-bending effects. He became a life-long advocate for proliferating his “problem child”, LSD, as a spiritual aid:

[LSD] is just a tool to turn us into what we are supposed to be

…

I see the true importance of LSD in the possibility of providing material aid to meditation aimed at the mystical experience of a deeper, comprehensive reality.

Hofmann’s clout as an accomplished scientist (rather than heathen native, weird occultist or far-out artist) would lend LSD a new flavor to the public among these substances. Sterilized, LSD proved ripe for research and understanding rather than reflexive condemnation. A group of advocates would form among scientists and intellectuals seeking to proliferate these fascinating newfound tools starting in the early ‘50s.

Psychiatrist Humphry Osmond pioneered research on the effects of LSD and mescaline on the mind. Early research centered on hallucinatory effects, likening the experience to temporary, induced schizophrenia. As study continued, focus shifted towards mind-expansion and capacity to bring spiritual experience.

Perhaps most important to the framing of psychedelics to common Western perceptions was writer Aldous Huxley, with whom Osmond collaborated. Steeped in Vedantic meditative mysticism, the already-famous writer requested access to the substance. Osmond accepted, supervising a 1953 mescaline trip. In ‘56, with insights gained from the collaboration, Osmond promoted the term ‘psychedelic’ to describe this new class of chemical substances, deriving it from the Greek words for mind-manifesting.

The appropriate term stuck.

Bursting Open the Doors of Perception

If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is: Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro' narrow chinks of his cavern.

From William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790), inspiration for Huxley’s psychedelic title

In ‘54, Huxley published the seminal title, The Doors of Perception, describing the “sacramental vision” he’d derived from mescaline, captivating readers and inspiring a generation of beat writers and artists.

Huxley described “seeing what Adam had seen on the morning of his creation — the miracle, moment by moment, of naked existence.” Breathing life and meaning into his telling, poetry, Huxley’s fitting account anchored Western conceptions of these heady experiences.

Disputing notions of harmful and crazed inebriation, Huxley depicts instead valuable spiritual discovery and noble truth-seeking, ecstatic as it is. Because mindset is so critical to psychedelic experience, Huxley’s conceptions proved thoroughly influential, remaining so today. Jim Morrison’s The Doors even named their band after Huxley’s title.

With insight derived from the psychedelic experience, Huxley expounded upon Blake’s notions regarding perception and consciousness.

To make biological survival possible, Mind at Large has to be funneled through the reducing valve of the brain and nervous system. What comes out at the other end is a measly trickle of the kind of consciousness which will help us to stay alive on the surface of this particular planet. To formulate and express the contents of this reduced awareness, man has invented and endlessly elaborated those symbol-systems and implicit philosophies which we call languages. Every individual is at once the beneficiary and the victim of the linguistic tradition into which he or she has been born -- the beneficiary inasmuch as language gives access to he accumulated records of other people's experience, the victim in so far as it confirms him in the belief that reduced awareness is the only awareness and as it be-devils his sense of reality, so that he is all too apt to take his concepts for data, his words for actual things.

. . .

[Under the influence of mescaline . . .] As Mind at Large seeps past the no longer watertight valve, all kinds of biologically useless things start to happen. In some cases there may be extra-sensory perceptions.

Other persons discover a world of visionary beauty. To others again is revealed the glory, the infinite value and meaningfulness of naked existence, of the given, unconceptualized event.

In the final stage of egolessness there is an “obscure knowledge” that All is in all – that All is actually each. This is as near, I take it, as a finite mind can ever come to “perceiving everything that is happening everywhere in the universe.”

The doors of perception cleansed under the influence of mescaline, Huxley now viscerally discerns abstract from material, beyond the language defined by other’s experience. There, he catches a glimpse of the infinite and eternal, perceptible only when the ego dissolves.

With the experience demonstrating that senses and perceptions have evolved as tools of survival, Huxley transcends the survival-mode of everyday life. Then, language becomes a curse. While one benefits from the wisdom of previous human experience in language, useful for survival, it also “petrifies” awareness of the reality one experiences, limiting consciousness.

The psychedelic experience, contends Huxley, allows one to shed those biases and mental shortcuts, adaptions however useful normally, to experience the world more directly and freely. Illustrating the valuable spiritual distinction between lived experience and abstract forms, the experience expanded Huxley’s consciousness. Evoking a variation on Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, Huxley contends the mescaline trip helped him viscerally experience the truth of pure daylight, the eternalness and interconnectedness of all.

Following Huxley, Alan Watts, already an established figure bringing Eastern spirituality to Western audiences, dipped his toes in psychedelia. Watts would also demonstrate profound clarity on psychedelic experience and its spiritual relevance in the 1958 The New Alchemy and the 1962 The Joyous Cosmology, helping to frame conceptions for the hippie generation ahead. In a related lecture, Watts described his psychedelic experience:

Lo and behold, I had what I simply could not deny being an experience of cosmic consciousness, the sense of complete fundamental total unity forever-and-ever with the whole universe. And not only that, but that what this thing was fundamentally—despite every thing and every kind of appearance in ordinary life to the contrary—that the energy behind the world was ecstatic bliss and love.

Similarly to Huxley, psychedelics conjured in Watts a wholly profound spiritual experience, a blissful sense of eternal unity and interconnection. Cool stuff.

The Spiritual Opening

With Nietzsche‘s 1882 finding that “God is dead,” Western spirituality and morality yearned for evolution, at least among many intellectuals. Scientific observations from the Age of Reason had disproven so much ancient dogma, the believability of traditional Christian mythology (taken literally) had waned, along with other ancient belief systems.

Of course, not everyone would be seeking a radical reappraisal of the spiritual status quo. It takes some serious backbone to disturb that most fundamental apple cart (or maybe a deep chip on one’s shoulder.) Many faithful remained of course, often deferential to church leadership on moral matters. Meanwhile, interested institutions and their leadership resist threats and often fight change — not just labor unions and industry groups, but churches too.

The occult movement gaining so much traction at the turn of the 20th century demonstrates an appetite to try something radically different, among a subset at least. The outraged public reaction to their antics however, including mescaline use, demonstrates the limits of this opening. Only a tiny minority would take seriously “The Wickedest Man in the World” for advice on salvation, for example.

Far more embraced (or caved to) fascism, unfortunately, which nearly all Christian churches failed to publicly reject during its rise. Worse yet, Pope Pius XI significantly supported the rise of Mussolini and Italian Fascism (but not Nazism in Germany.) The German Catholic Church apologized in 2020 for its complicity, failing to say “no” and lending legitimacy to the Nazi war effort. The German Christians movement pushed for the unification of the German Protestant churches under one pro-Nazi, antisemitic outfit, the German Evangelical Church. Their efforts were mostly successful, backed by intimidation and state power, but also caused many schisms. Some of the brave, opposing priests ended up in concentration camps.

Church leadership and the Fascism movement in Europe shared several interests: namely deep fear and rejection of (atheistic) communism, preference for strict hierarchy, distrust of relatively new liberal governance and distaste for nonconformity. But also, Christian dogma is reticent to buck state power — “Render unto Caesar” after all.

The Catholic Church would take a neutral stance on the Holocaust, born from an impulse to protect itself, to keep its Churches open in Germany (and everywhere else should the Nazis have prevailed.) Feeling existential threat, nationalist attitudes and institutional interest apparently overwhelmed Christian morality (again.)

Moreover, Christian leadership and fascists shared interest in promoting the “sacralization of cultural identity“ in Europe. That is, interest and bias emerged to frame anything positive or dominant as Christian, while framing things negative and countercultural as Jewish and Marxist. This long-time dynamic would run away from the church carried by Nazi propaganda into something far more sinister and dangerous.

The Holocaust easily represents the most severe spiritual failure of 20th century Europe. Morally speaking, Hilter’s Ubermensch reigned supreme . . . able to do so in part by co-opting the Church.

After the horrors of WWII, the spiritual opening now wider with this massive failure, Joseph Campbell like Nietzsche before him lamented the lack of unifying mythology in the then-modern world:

The first condition, therefore, that any mythology must fulfill if it is to render life to modern lives is that of cleansing the doors of perception to the wonder, at once terrible and fascinating, of ourselves and of the universe of which we are the ears and eyes and the mind.

Borrowing Blake and Huxley’s ‘doors of perception’, Campbell contends that successful mythology brings the Universe to life, in all its wonder and terror. It illuminates the individual’s relationship to it. Successful mythology must be compelling.

Similarly, Alan Watts noted that the mystical experience broadly “is nothing other than becoming aware of your true physical relationship with the universe. And you are amazed, thunderstruck . . . the fundamental thing is a state of unbelievable bliss.” This is precisely how both Huxley and Watts described portions of their trips — bona fide mystical experiences. Watts would suggest these are just like those ‘legitimately’ conjured with any number of meditative or mystical traditions.

Seems to be just what the doctor ordered.

In the other early accounts discussed here, it seems important to reiterate a few were unpleasant, with at least one psychologically damaging. Poor Satre and his mind crabs — these experiences come with risks. But nearly all noted the psychedelic experience delivered meaningful insights. For Crowley, the experience proved so profound, it inspired in him a new religion. This would become much of the inspiration for New Age spirituality that took off decades later in the 60s-70s when psychedelics hit pop culture.

Early Western psychedelic epiphanies illuminated the nature of perception, highlighted individual’s relationship to the Universe, countered addictions and aided in bucking pressures of conformity. Mind-manifesting indeed, psychedelics proved powerful spiritual aids as they escaped containment. Not just for spirituality, curiosity and boosting creativity drove many. Also heavily stigmatized, mescaline attracted mostly fringe players and dedicated truth seekers: painters, psychologists, philosophers, poets and occultists.

Among this early group, only Crowley seemed particularly provocative. The others all acted in private and discreetly. Those who publicly shared their accounts mostly did so without purposefully poking eyes and ruffling feathers, with seemingly noble intent. With slow proliferation, the early few that experienced these sacraments acted responsibly and non-threateningly for the most part.

By the mid-60s, though, as psychedelics crashed onto the mainstream, the dynamic would change dramatically — countercultures and fringe figures would kick ass and take names, again threatening the spiritual Establishment.

Thanks for reading! Stay tuned for Part 3 where we’ll get into psilocybin proliferation and the 60s, Tim Leary, Dick Nixon and the War on Drugs.

“And you are amazed, thunderstruck . . . the fundamental thing is a state of unbelievable bliss.”

Watts’ quote here is THE unifying characteristic of all people who have experienced spiritual enlightenment. The unenlightened masses do not react positively to this sort of talk. Despite the very real and meaningful breakthrough experience of enlightenment, those same limitations of language apply—when it’s time to tell the normies about it. This is why it’s so easy for “society” (read: boring fucking normies who are generally miserable) to reject it. For one, they can’t see to through to the place they’ve never been, so the kneejerk reaction is to hate on it; for two, the language of “society” limits what the enlightened people can say. Even Watts’ quote above suffers from this very real and meaningful limitation, and ends up sounding—to the unenlightened masses—like self-help book psychedelic hippie-dippie drug babble. The doors of perception might as well be brick walls to them. Much, MUCH easier to concoct some ridiculous bullshit rooted in their more base values: like prosperity gospel. People eat that shit up! Why? Because it avoids the brick-wall doors of perception entirely, and instead appeals to, ahem, more earthly desires. Talk of “unbelievable bliss” won’t pay the bills: of yourself or the unenlightened masses whose dollars you covet. No, no, no. Better to invent some completely false nonsense like “Jesus wants you to be rich.” THAT is the kind of faux-enlightenment you can take to the bank. It taps into unenlightened people’s only “mystical” dogma they’ll accept—the ever-present “Judeo-Christian values,” and their very, VERY not-mystical base urges for material wealth. “So I can praise Jesus AND get rich?!? Hot damn! Why didn’t anyone tell me sooner!”

Someone please dose Joel Osteen’s communion wine.